In late September, police in Campbell River issued an urgent warning: at least eleven people had died from suspected drug overdoses in just five weeks.

On paper, it’s another tragic local story in British Columbia’s long, unrelenting overdose crisis. But for the people who live there — and for anyone paying attention — the message is much bigger. It’s a warning about how fragile our systems still are, and how quickly things can unravel when access to care, community, and safety falls apart.

A Community in Crisis

Police described the sudden surge in deaths as “deeply concerning” and called on residents to spread the word to “prevent further loss of life.” Island Health issued a concurrent Drug Poisoning Overdose Advisory, urging people not to use alone, to get substances tested, and to use overdose prevention sites when possible.

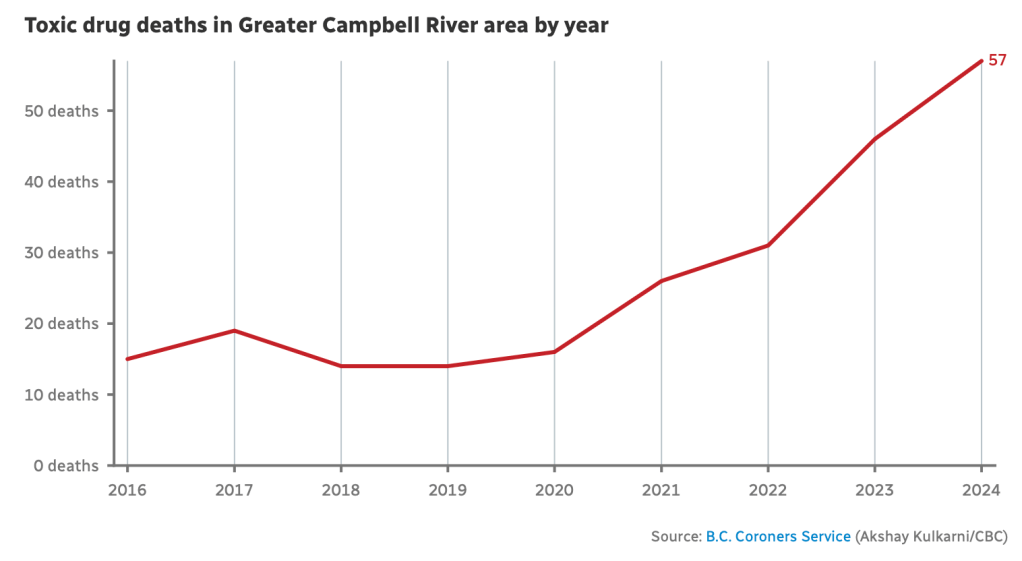

According to Dr. Charmaine Enns, North Island Medical Health Officer, the recent deaths are “a continuation of what has been happening for nearly a decade due to the unregulated drug toxicity crisis.” The phrasing matters. This isn’t a new wave — it’s the same storm we’ve been weathering for years, made worse by a poisoned, unpredictable supply and gaps in our response.

When the Safety Net Weakens

Local outreach worker Sue Moen, coordinator for the Campbell River Community Action Team, told CBC News that the situation reflects both policy and community failures.

“The community is reeling,” she said. “We are, in many, many ways, feeling hopeless and helpless.”

Moen pointed to the recent closure of a drop-in centre and community kitchen — spaces where people used to check in on one another, share meals, and stay connected.

“The loss of those spaces means that people are more dispersed,” she explained. “We are seeing a lot more hunger in the community, which is contributing to more ill health, which … when you combine that with the toxic drugs, the adverse reactions and overdoses are more severe.”

When services disappear, so does safety. Isolation grows. People begin using alone again — a leading factor in fatal overdoses.

Policy and Supply: A Volatile Equation

The Campbell River RCMP said the local drug supply appears “volatile,” and it’s still unclear which substances or contaminants are behind the deaths. Toxicology reports will take time, but the pattern is painfully familiar. Fentanyl contamination continues to drive the vast majority of overdose fatalities in B.C., and newer, more unpredictable compounds like benzodiazepines are making the street supply even deadlier.

Meanwhile, recent changes to the B.C. safer supply program have introduced new barriers to access. Under the revised policy, individuals prescribed safer opioids must consume them in view of a pharmacist — a rule that is nearly impossible to follow in smaller towns like Campbell River, where pharmacies are few and stigma remains strong.

Moen argued that these restrictions contradict the intent of safer supply: “If both the government and the medical community are going to talk about this as a health problem, then they have to have evidence-based health solutions.”

Her words cut to the heart of a long-standing contradiction — we call addiction a medical condition, yet still manage it like a criminal one.

The Unregulated Supply

Dr. Enns told CBC’s Gregor Craigie that as long as the drug supply remains unregulated, “we are not going to get in front of this.” She added that education and awareness campaigns alone won’t stop deaths when the drugs themselves are unpredictable. “We have to deal with the supply first and foremost.”

That means addressing what people are actually using, not just telling them not to. Drug checking services exist in B.C., but they are often underfunded or hard to access outside of major cities. Many of those dying are not connected to services at all — due to stigma, fear, or lack of information.

It’s a grim but honest assessment: until the supply is safer, the cycle of warnings, advisories, and grief will continue.

Compassion as Public Policy

Moen’s perspective is especially telling: “For any other disease — cancer, diabetes, Parkinson’s — we would never dream of withholding the essential medications that those people need. And yet, for more than 100 years of prohibition, that is the tack that we have taken with people who use substances.”

That comparison isn’t rhetorical. It’s an appeal for consistency — to treat substance use disorder like the chronic, treatable condition that science says it is.

Expanding safer supply, scaling up detox and voluntary treatment, and rebuilding lost community infrastructure aren’t radical ideas; they’re the baseline for public health. As Moen put it, “If we’re going to call it a health problem, then we need health-based solutions.”

What Campbell River Teaches Us

Campbell River isn’t the first B.C. city to experience a spike in overdose deaths, and sadly, it won’t be the last. But the tragedy reveals how fragile progress can be — how one change in local policy, one shuttered service, or one misjudged reform can ripple through an entire community.

These eleven deaths in five weeks are not random. They are symptoms of an ongoing system failure — one that punishes vulnerability, underfunds support, and treats survival as luck instead of a right.

Until that changes, every “public warning” will come too late.