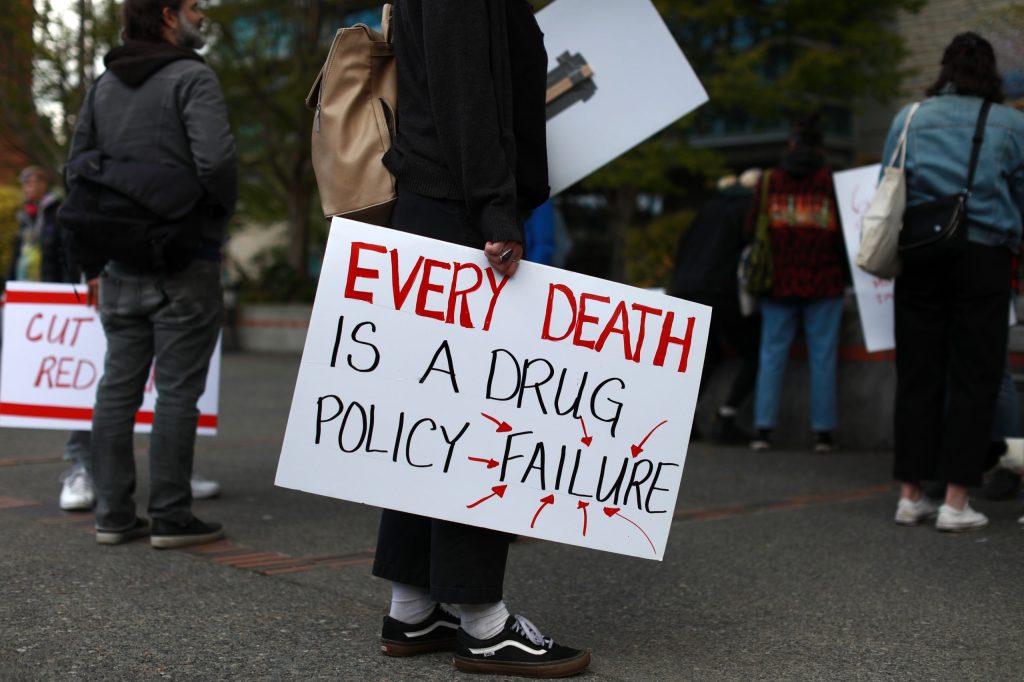

Criminalizing people who use drugs carries real consequences beyond legal penalties. It affects health, social standing, access to supports, dignity, and even survival. In British Columbia, this has been especially visible amid a decades-long toxic drug crisis. Since decriminalization (possession of small amounts without criminal charges) came into effect, we’ve begun to see what happens when we ease some of that criminal burden. But the human cost of what we had before (and what we still have) is still very much present.

What Criminalization Meant (Historically & Recently) — The Harms

Here are concrete ways criminalizing drug possession has harmed people in BC:

- Stigma, Fear & Isolation

- Criminal records can follow individuals, making it harder to get employment, housing, or maintain family relationships. These ripple effects exacerbate poverty and marginalization.

- The shame or fear of arrest, criminal charges, or drug‐seizure can discourage people from seeking help, medical care, or overdose prevention. BC government documents state that decriminalization aims in large part to reduce stigma and fear of criminal prosecution that prevent people from accessing health supports.

- Legal Penalties & Interactions with Police

- Before decriminalization, possession of small amounts meant risk of arrest, seizure of drugs, and criminal charges. Cumulatively, even “minor” offences carry large consequences.

- Evidence from BC’s early report: after decriminalization, possession charges dropped ~76% from past averages (past four years) in the first year.

- Health Harms

- Use in isolation: People using drugs alone (to avoid detection or arrest) are at higher risk of fatal overdose. Criminalization makes people less likely to use supervised consumption sites or seek overdose prevention services. BC policy documents explicitly mention that fear of criminal penalties pushes drug use into spaces where overdoses are less likely to be witnessed or reversed.

- Delays in care: Medical systems are safer spaces than criminal ones for treating addiction, yet fear of legal consequences has blocked or delayed entry into treatment for many.

- Social & Economic Exclusion

- Criminal convictions can exclude people from stable housing, professional licensing, or even certain social supports.

- For Indigenous communities and people who are already marginalized, criminalization often compounds other inequalities. In BC, overdose death rates and harms disproportionately affect First Nations people.

- Mental Health & Trauma

- Encounters with the criminal justice system (arrests, court appearances, incarceration) are themselves traumatizing.

- The psychological toll of living in fear of prosecution, socially ostracized, or in hiding adds strain: increasing anxiety, depression, shame, which can worsen substance use.

What Decriminalization Has Changed (And What Remains)

BC’s pilot decriminalization has shown measurable shifts:

| Change | What it’s done |

| Fewer criminal justice interactions | A Dalhousie University study found a ~57% drop in police incidents involving people who use drugs after decriminalization. |

| Huge drop in possession charges | ~76% reduction compared to past averages |

| Drug seizures reduced | Seizures dropped by ~96% in early months of the change |

| More use of harm-reduction services | Drug checking service use increased ~60%, more visits to overdose prevention/supervised consumption sites. |

But there are also gaps and ongoing human costs:

- Public drug use & public safety concerns: In May 2024, BC “re-criminalized” (or reintroduced legal restrictions) public possession/use in certain public spaces, after concerns from the public and government about disorder. So the benefit isn’t uniform in all contexts.

- Knowledge gaps: Before decriminalization, and even after, many people who use drugs did not fully understand the policy (what drugs are covered, what amounts, what rights). This weakens the ability to benefit.

- Still high rates of overdose deaths and hospitalizations: Decriminalization (so far) has not resulted in a significant decrease in fatal overdoses or hospitalizations due to opioids or stimulants in its first year vs comparison to previous years. I’m not saying it failed — the policy may take time, and there are other factors (toxic supply, homelessness, etc.). But criminalization’s removal isn’t a silver bullet.

Human Stories & What Doesn’t Show Up in the Numbers

Beyond numbers, there are lived effects that stats can’t always capture, but which paint the cost clearly:

- People avoiding carrying naloxone or other emergency supplies because they fear police interactions.

- Drug users who are unhoused having to hide their use, leading to more secretive use, making overdose reversal less likely.

- Barriers when someone with a criminal record tries to access housing, or child custody, or jobs.

- Embarrassment, shame, social isolation — pulled away from community supports, family, friendships.

These human effects may show in mental health trends, increased risk of other harms (infections, injuries), worsening of physical health and quality of life.

Why Criminalization Is Still a Problem (Even with Partial Decriminalization)

Even now, criminalization’s legacy persists:

- Legal and social stigma remain deeply rooted; people still fear judgment or repercussions.

- Some public spaces still criminalize possession/use (per recent amendments). That means people can still be arrested, which undermines consistency.

- Unequal understanding of rights; not everyone knows what’s allowed or not. So people may get caught out unintentionally.

- Toxic unregulated drug supply remains deadly; policies that reduce legal penalties don’t fix supply side risks.

What Human-Centered Policy Looks Like

To reduce human cost further, here are what evidence suggests we need:

- Clear information & legal education for people who use drugs: knowing what is legal, what rights exist, when police can act, etc.

- Expand harm reduction and health services, accessible and non-judgmental:

- More overdose prevention, supervised consumption sites, drug checking.

- Safe supply options.

- Outreach and housing supports, especially for marginalized groups.

- Address social determinants: housing, poverty, mental health, trauma, stable income. Criminalization often compounds these issues rather than resolving them.

- Continued monitoring, evaluation, adjustment: track not just legal incidents but health outcomes, overdose deaths, hospitalizations, but also quality of life, stigma, social inclusion.

- Policy coherence: ensure changes to public space rules, law enforcement guidelines, and support services are consistent; avoid patchwork that leaves certain people exposed to criminalization still.

Criminalizing people who use drugs in BC has carried heavy human costs: stigma, isolation, legal penalties, interrupted access to care, and often worse health outcomes. Decriminalization (even partial) has already demonstrated some relief: reduced arrests, less fear, more use of harm reduction services. But it’s only part of the puzzle.

To truly reverse the harms, policy needs to be built around compassion, public health, and social justice. We must hear and centre the voices of those most impacted, invest in health and supports, and keep pushing for consistency.